ORÐ OG BREYTNI Í BARÁTTU FYRIR MANNRÉTTINDUM

Í dag flutti ég erindi hjá Institute of Cultural Diplomacy í Berlín um alþjóðalög og mannréttindi. Ég á sæti í svokallaðri Ráðgjafanefnd þessarar stofnunar, sem ég nokkrum sinnum hef greint frá hér á síðunni og þá jafnframt birt erindi sem ég hef flutt á hennar vegum.

sjá: https://www.ogmundur.is/is/greinar/institute-of-cultural-diplomacy

https://www.ogmundur.is/is/greinar/hvenaer-og-hvernig-a-althjodasamfelagid-ad-beita-ser-gegn-hernadarofbeldi

https://www.ogmundur.is/is/greinar/a-radstefnu-um-althjodastjornmal-i-berlin-verdum-ad-lydraedisvaeda-sameinudu-thjodirnar

https://www.ogmundur.is/is/greinar/raett-um-mannrettindi-i-horpu

https://www.ogmundur.is/is/greinar/radstefna-um-strid-frid-og-mannrettindi

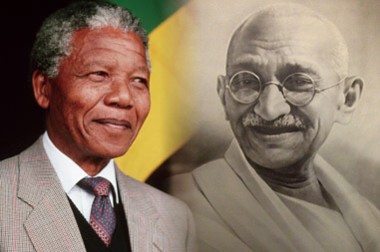

Venju samkvæmt birti ég nú erindi mitt, aðeins á ensku, því miður, en í erindinu geri ég að umræðuefni framlag tveggja manna, Mahadma Gandhi og Nelson Mandela til mannréttindabaráttu í heiminum.

Erindið birtist hér:

Human Rights-Based Approach as a Basis for Development, Justice and International Law" is the title to my talk.

This is a fitting title. At ICD conferences I have attended, since I became member of the Advisory Board of the Institute, and later in charge of developing our work on human rights, my talks have been concentrated on how the world could get out of the impasse it finds itself in with regard to human rights, especially in situations when nation states are not fulfilling their function of protecting their citizens. In this respect I have looked to the initiative originally taken when the government of Canada in 2001 established the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, to answer questions put forward by Kofi Annan, the then general Secretary of the United Nations, on the rights and responsibilities of states to interfere when human rights were being violated. The name of the report which the Convention produced was „Responsibility to protect".

In this report it was contended that a nation´s right to sovereignty should be respected, but when a state was unable, or unwilling, to protect it´s citizens, responsibility to do so should be tranfered to the international community.

In spite of good intentions by the United Nations, right from their establishment, just before the middle of the 20th century, to prevent war crimes with the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, nothing much happened for half a century and still, partly due to an outdated organizational structure of the UN, with a Security Council reflecting the power structure of 19th century colonialsim, the Cold War of the 20th century, and the world of superpowers of our day, nothing happens if the big stakeholders so decide.

Nevertheless, things are happening: The principle of Responsibility to Protect is gradually being established as a norm - not legally binding in international law as yet - but a norm nevertheless, that is being discussed and developed in the UN. Amongst those who have taken an initiative in this respect, indeed at the incentive of ICD, was Janez Jansa, former prime minister of Slovenia, who took the question formally up in the United Nations. And I might add that voices calling for the democratization of the UN are being more frequently heard as I have referred to in my former talks - myself urging such moves should be taken.

These have been core questions asked at ICD conferences and I think it is important that we do our utmost to stimulate this dicussion and move it forward by encouraging individual states to look at their own legal frameworks and by taking initiative steps internationally to influence changes in international law for the benefit of human rights.

This very day we look powerless on Syria, where millions of people are being uprooted, and subjected to terrible human rights violations, likewise in many countries in Africa, in Palestine, where I have experienced human rights violations, as a direct onlooker on a visit to the occupied zones that I will never forget. I also mention Nagarno Karabach where hundreds of thousands of people have been uprooted, causing enormous hardship... and the list goes on.

This has been the subject of our discussions at the conferences I have attended in the short period I have been with ICD. I have witnessed an expansion, or shall I say explosion, of our activities. At our December conference last year, many I spoke with, expressed a combination of surprise and admiration for the remarkable success of ICD in recruiting an ever larger group of prominent politicians, academics, artists, activists into its network.

At the Advisory Board meeting in December there were, however, voices raised that we needed more direction, that we must become more precise in our objectives. Of course I agree that it is important always to know exactly where one is heading and I am glad to have the opportunity at this seminar with the ICD team and students to discuss exactly this. And I also agree with a friend at ICD, who said to me when I expressed enthusiasm and told him I found what we were doing to be exciting. "In my mind", he replied, "it is not about being part of an exciting exercise, I want results!" And he added: "We don´t live forever and I want to see in my lifetime changes of improvement to take place. It is an urgent task."

So many were those words. He is a man from Israel and does not want future generations to be subjected to the abnormalities of life and the war mentality of the past. This is right. We want success. But how is success to be achieved?

ICD, as I see it, is about method. And I think it is important never to forget this. In the first place, it is about bringing people together, as we have been doing, bringing people together in a melting pot of ideas, getting inspiration and collective strength to proceed with our work. But it is also a question of a mind-set, an attitude. And what I would like to do this afternoon is to discuss, two success stories in this light, how success was achieved, in the face of violence and profound prejudice, in seemingly insurmountable circumstances. Maybe there is something to be learned.

To put it concretely: I want to ask how we can achieve human rights through discussion and peruasion; how we can transform prejudice - not by force, not by war, but through political and personal persuasion - through the method that lies at heart of Cultural Diplomacy.

And I want to start by asking a question.

Why is it that when Nelson Mandela dies the world reacts the same way; the whole world, exactly in the same way? Why?

The whole world mourns. There is no question about that. All men alike - whether they be rich or poor, selfish or generous. Everyone. I think we all mourn him because we all recognize him as a man of unique quality. A man who by his own deeds proved his humane message. That is why.

That was indeed how Mahadma Gandhi - the other part of my success story - had phrased it half a century earlier: „My life is my message", he said. These two men managed to touch a chord - a human chord that is common to us all. It could be said that they touched the chord of humanity. In their fight for human rights they set an example by their own life, thus transforming the prejudice they stood up against into a victory for their own cause.

There have been experiments in history to minimize the importance of humanity. Thus Communism was to become realized almost mechanically - historical materialism was seen to be in line with natural law. We, human beings were, indeed, seen to be instrumental, but only as instruments, tools; as mechanical tools in the inevitable march of history.

Capitalism is also, to some extent based on a mechanical view of history. Adam Smith´s "Hidden hand" would see to it that only if we paid respect to the law of the market everything would develop to the utmost good of society and mankind. Inspired by this way of thought; inspired by capitalist ideology, Margareth Thatcher, the Iron Lady of Great Britain, said famously - or should we say infamously, "greed is good!" According to her ideology, greed was the driving force of history and no harm would be done by encouraging greed and self-interest, since the "hidden hand" , the inherent laws of capitalism would ensure that all would in the end turn out well!

It cannot be said that this approach has made the world better or more peaceful. People wage wars because of greed and the longing for profit and power. The development of human history is after all, characterized by material interest of this kind. And here we have a vicious circle being formed. A man kills another man because he covets something in the latter´s possession. The third takes revenge. This, the brokers of power politics follow as animals of prey. They have learned how to turn to their own end, fear, prejudice, hatred, the longing for avenge. Their interest is to maintain conflict and tension - and the fires of hatred burning. No better are the guardians of political truth! Even if the goals, envisaged by self-proclaimed experts in human development, may sometimes have been morally commendable: A heaven of equaliy and justice for all - and for that matter just round the corner - this approach to life has turned out to lethal. The more certain you are of the coming heaven, the more dangerous you are!

An -ism, to my mind, is always dangerous, whether it be communism, capitalism or, indeed, belief in any other -ism.

The strange thing about the -isms is the way the historical players keep changing roles. We - and here I include myself - the ardent socialists of yesterday, tended to be ideological in our approach and the predecessors to my generation, who were in that political vein, were even more so. Always when socialist experiments or systems where criticized, the answer would always be the same: "Don'´t judge us and our policies harsh, because of failures. They are temporary. Be aware that we are creating a new world with new methods, new mechanisms, new laws and new values. When this world, our world, emerges - then judge us. Then practice will prove our theories to be right."

Of course this world never came to be - the fight for more equality and a more just society certainly bore fruit in many societies - but a human heaven on earth has not come into being. And now most of us - socialists - have given up belief in ideology and have turned to a more pragmatic, empiricist and utilitarian approach, in very much the same way as yesterday´s liberals and conservatives used to think.

In a sense the world has been turned upside down in this respect. Roles have been reversed. Now it is the capitalist marketers who have become the ideologues of our time. When advocating the benefits of privatizing health, energy and water, they answer our criticism by admitting that the promised results are yet to be realized. They urge us to be patient and wait until a perfect market is in place and functioning: "Remember," they cry out, " we are creating a new world!"

I mention this almost in passing, but to remind us that the ideological approach to life tends to be based on prejudice - indeed as the word itself indicates: Judging beforehand, judging before proper examination has taken place. And if you think you know you are right, there is the danger that you try to force your views upon others. The question then remains, what you in reality achieve, because if you are not changing the way society thinks and conceives itself, you have not made a lasting change, in fact you may have changed nothing at all and you certainly have not done away with prejudice, the fuel of injustice.

At one point in the 19th century, communists and anarchists debated how to revolutionize society. The former, advocated a revolution, whereby a framework was to be created by force which in turn would lead to the desired end. In other words, first you create a box we can call perfect society and then you put freedom and justice into that box. Many anarchists had grave doubts about this and maintained that the method of change was all important. A system created was always a reflection of the method it was created by. You could never create a free and just society by force.

Both Mahadma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela had a clear vision. But it was based on self-restraint and self-sacrifice, showing by deed the moral superiority of non-prejudice.

Gandhi´s seven social sins were the following:

Politics without principles

Wealth without Work

Pleasure without Conscience

Knowledge without Character

Commerce without Morality

Science without Humanity

Worship without Sacrifice

The last mentioned social sin, worship without sacrifice, is in my mind of crucial importance to Gandhi´s philosophy because it has to do with you and I, "as the message", to use Gandhi´s phrase. It has to do with our responsibilities and conduct as individuals. Each and every one of us. And here there is a strong correlation between Gandhi and Mandela.

Richard Stengel, the editor of Time magazine interviewed Nelson Mandela for his book Mandela´s Way. There Stengel tells of Mandela - who, let us not forget, was in his earlier days the leader of the military wing of the African National Congress, the ANC, the freedom fighters in South Africa.

I quote Stengel: "Prison was his great teacher. It burned away a lot of his character, a lot of the youthful impulsiveness and recklessness, and taught him incredible self-control, because in prison that was all he could control. There was no room for outbursts or self-indulgence or lack of discipline. I used to ask him, over and over, how prison had changed him. This question annoyed him. He either ignored it, went straight to a policy answer, or denied the question. Finally, one day, he said to me in exasperation, ‘I came out mature'. By maturity, he meant that he learned to control those more youthful impulses, not that he was no longer stung or hurt or angry. It is not that you always know what to do or how to do it, it is that you are able to tamp down your emotions and anxieties that get in the way of seeing the world as it is. You can see through them, and that will see you through. Mandela thought Africa needed discipline and self-control, and he wanted to be a guiding light for Africa in his own self-conduct. ... As Gandhi once put it, "real home rule is self-rule or self-control." By showing that they could control themselves even in ... exasperating and provocative conditions, these great leaders took away the excuse that others used to rule them and their people."

Of course these men were not alone. Desmond Tutu´s power of persuasion was of monumental importance. His message was of course a Christian one, being a religious man and a bishop. But it is interesting to learn that Ubuntu, an African philosophical heritage also influences both Tutu´s and Mandela´s vision and this has to do with community, to see the particular in the light of the whole, the individual as part of society where everybody belongs.

Tutu explained Ubuntu in these words:"Ubuntu speaks particularly about the fact that you can't exist as a human being in isolation. It speaks about our interconnectedness. You can't be human all by yourself, and when you have this quality - Ubuntu - you are known for your generosity.

We think of ourselves far too frequently as just individuals, separated from one another, whereas you are connected and what you do affects the whole World. When you do well, it spreads out; it is for the whole of humanity."

Desmond Tutu has further described this perspective by saying that, Ubuntu ‘is not, "I think therefore I am." It says rather: "I am a human because I belong. I participate. I share...In essence, I am because you are."

( cf.Cogito ergo sum, as Descartes said, I think therefore I am)

Awareness of society is here at heart. And if you want to have an influence on how we think and how we act you must direct all your endeavor towards society; you try to influence the way it thinks not only by talking, and persuading, but by your deed.

At Nelson Mandela´s memorial, United States President, Barak Obama, spoke about Ubuntu, and I quote:

"There is a word in South Africa -- Ubuntu -- a word that captures Mandela's greatest gift: his recognition that we are all bound together in ways that are invisible to the eye; that there is a oneness to humanity; that we achieve ourselves by sharing ourselves with others, and caring for those around us.

We can never know how much of this sense was innate in him, or how much was shaped in a dark and solitary cell. But we remember the gestures, large and small -- introducing his jailers as honored guests at his inauguration; taking a pitch in a Springbok uniform; turning his family's heartbreak into a call to confront HIV/AIDS -- that revealed the depth of his empathy and his understanding. He not only embodied Ubuntu, he taught millions to find that truth within themselves."

For us, all this is of importance to consider as we seek ways of dealing with human rights violations past and present. Umbutu is a concept worth considering in this context. It is recognised as being an important source of law within the context of strained or broken relationships amongst individuals or communities and as an aid for providing solutions which contribute towards mutually acceptable remedies for the parties in such cases. It is to be contrasted with vengeance. And "redemption" is an important part of this philosophy. It relates to how people deal with deviant and dissident members of the community. Any imperfections should be borne by the community and the community should always seek to redeem a man.

But where does this lead to? Should all errant behavour or misdeeds and indeed serious crimes be forgiven and the perpetrators "redeemed"?

Mandela realized that the problem with vengeance or retribution is that it could lead to a more extensive response than punishment. It could not only engender more violence; it could allow the perpetrators to transform themselves into victims. Thus, retribution also needed limits because it could create new bloody conflicts. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in South Africa was about a societal reconciliation through the rehabilitation of both the victim and the perpetrator, who should have the chance to be reintegrated into society based on a pardigm change-the shift from white minority rule to black majority rule. Forgiveness allows victims to reassert their own power and reclaim their dignity. It also shows the wrongdoers the effects of their unjust actions. To be able to transform a criminal, forgiving depends on a process that must be shared by the forgiven and forgiver. An admission of guilt is the precondition for forgiveness. If successful, the process rehabilitates the perpetrator and restores self-respect to the victim. Yet, pardon does not transform all perpetrators.

Making contrition a precondition for it, increases the likelihood that contrition will be faked. Even if expressions of regret and remorse are usually vital to an apology, an apology cannot undo what was done. Hence, it is bound to be insufficient. Forgiveness is and must remain unpredictable. This is the only way to retain the power to grant or withhold it. Only the victim, not the state, can grant an apology.

Here it must be said that while restorative justice is meant to elicit truth, accountability, and reconciliation, it is not necessarily just. The underlying premise is often tied to another equally important element: political stability. It often benefits the perpetrators and fails to offer redress to victims.What is then the lesson to be drawn, as regards the question we are dealing with, namely how to transform prejudice and achieve human rights through personal/political persuasion.

Mandela reached out to those who were stuck in their prejudice and had labelled him a communist and a terrorist in order to divert attention from all that mattered, the oppressive apartheid system. Mandela fought a political battle, but it also was a personal battle, his struggle was more than a political dogma, let us never forget that. In order to become more than a battle of political ideology, it must have a personal content, self-restraint by the individual and possibly sacrifice, making it more than academic superficiality.

It was sacrifice which made Gandhi and Mandela the leaders they were - their victory could not be separated from their sacrifice - it was part of the same process. By restraining selfishness and greed, controlling themselves as individuals, they influenced politics at large - they made politics principled!

The lesson to be drawn is that in fighting prejudice - the oil on the fire of hatred, which is kept alive for the benefit of the few, the greedy and the seekers of power - we need to heed the examples set by these great moral giants and listen to their language; the language of cultural diplomacy.

Cultural diplomacy aims at changing the way the world thinks. And this is our task: To contribute to change the way the world thinks.

This we all understand because in all of us there is after all the same human chord; the chord of humanity. It only awaits to be touched.